„Alternative Porn“ und ästhetische Empfindsamkeit

Indie-Porn stellt ein derzeit florierendes Subgenre der Pornografie dar, in dem wohl bekannte Looks aus Subkulturen wie Gothic oder Punk oftmals in anti-kommerziellen, feministischen Selbstermächtigungsgesten inszeniert werden. In dieser Hinsicht werden die Konflikte, welche die Debatte um pornografische Obszönität seit den sechziger Jahren prägte, jedoch zugunsten alternativer Sexualästhetiken vermieden – Pornografie verliert so eines ihrer grundlegenden Merkmale. Aber kann es Pornografie jenseits des Öbszonen überhaupt geben?

Der Widerspruch fast aller Pornografie ist ihre Zerstörung des Obszönen. Wie das Schöne für den Klassizismus, das Erhabene für die Schauerromantik und das Hässliche fürs Groteske ist das Obszöne ästhetisches Register des Pornos, seine Aura und sein selling point. Sade erfindet die moderne Pornografie an einer historischen Schwelle von regelpoetischer poiesis und empfindsamer aisthesis in den Kunstlehren. Die „120 jours de Sodome“ illustrieren genau diesen clash of cultures: eine Täterriege alter Aristokraten, die ihre Orgien regelpoetisch kombinieren und choreografieren, eine Opferriege junger Bürgerkinder, deren Empfindungen die Ausschweifung als Perversion erst sichtbar machen, und als Resultat eine wechselseitige Eskalation von poiesis und aisthesis, Konstruktion und Empfindung, Maschine und Körper. Vollständig entwickelt sind hier bereits Konzeptualismus und Performance als widerstrebend-komplementäre Pole moderner Kunst, wieder aufgenommen wird ihre pornografisch-maschinelle Verkopplung in Duchamps „Großem Glas“ und Schwitters „Merzbau“, großbürgerliche Sexmaschinenkonstruktion und kleinbürgerlich-empfindsame „Kathedrale des erotischen Elends“.

Dass die pornografische Logik des obszönen Tabus sich nirgendwo konsequenter aufhebt als in der Pornografie selbst, zeigen beispielhaft die Performances von Annie Sprinkle. Als Darstellerin in Siebziger-Jahre-Mainstream-Pornos, die Aktionskünstlerin und „Alternative Porn“-Pionierin wurde, überschreitet sie nicht nur Genre-Grenzen, sondern stellt auch die klassische heterosexuell-pornografische Bildkultur auf den Kopf. Mit ihrer rituellen Einladung ans Publikum, ihr per Spekulum in die Vagina zu blicken, schließt Sprinkle die ikonografische Tradition von Courbets „L’Origine du Monde“ (1886) und Duchamps „Étant donnés“ (posthum 1968) ab, entschärft dabei jedoch den vormals geilen Blick und treibt, als Aufklärerin im zweifachen Sinn, dem Anblick Tabu und sexuelles Mysterium aus. Wenn die Schriftstellerin Kirsten Fuchs von obszöner „Wucht der Sprache“ spricht und ,,in einem Wort wie ‚Fotze‘ […] viel Kraft“ entdeckt,1. so benennt sie nicht nur das Tabu von Indie-Porno-Diskursen, die diese Wucht entschärfen, sondern auch das Scheitern industrieller Pornografie, sie zu reproduzieren. Sade, dessen systematisch konstruierte Eskalationen so abstumpfen wie jede Mainstream-Pornografie, versucht, das Tabu zu retten, indem er den Exzess bis zur rituellen Tötung treibt, eine im Kern romantisch-sentimentalische Denkfigur, die in den „urban legends“ der Performancekunst-Selbstmorde Rudolf Schwarzkoglers und John Fares fortgeschrieben wird und die Genesis P. Orridges im Wettlauf gegen den Zeitgeist stets weitergetriebene Körpermodifikation auch physisch vollzieht.

Die „Exploitation“ der Pornozuschauer besteht darin, ihnen Obszönität falsch zu versprechen oder – wie der Gonzo-Porno seit John Staglianos „Buttman“-Serie – sie durch aggressive Penetration und Ausstülpung von Körpern zu simulieren.2. Genau darin treffen sich jedoch Mainstream- und Independent-Pornografie, Porno-Business und -Aktivismus: Sprinkles Performances sind Gonzo mit feministischem „Empowerment“, der die Ausgestülpte wieder zum Subjekt macht. Und jene Independent-Pornografie, die sich seit kurzem und vor allem im Internet als Genre etabliert hat und durch sexuell explizite Autorenfilme wie „9 Songs“ und „Shortbus“ flankiert wird, kann auch deshalb ohne schlechtes Gewissen diskutiert werden, weil sie „guten“ Sex ohne Obszönität darstellt. So löst sich, nach Unterbrechungen durch die feministische Anti-Porno-Debatte der 1980er Jahre, Peter Gorsens Befund einer neovitalistischen Tendenz in zeitgenössischen Sexualästhetiken ein, die das Programm der Lebensreform- und Freikörperbewegung vollenden.3.

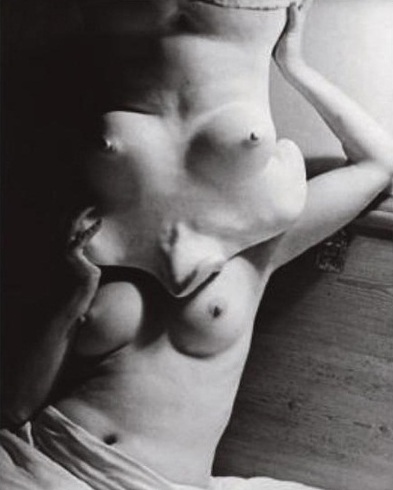

Damit verschwimmen auch die Grenzen pornografischer Ausbeutung subkulturell-experimentalkünstlerischer Codes einerseits sowie subkultureller Aneignung pornografischer Codes andererseits. Die australische Pornoholding gmbill.com betreibt mit dem „Project ISM“ auf ishotmyself.com eine Website als simuliertes Konzeptkunstprojekt von Frauen, die sich selbst fotografieren, und mit beautifulagony.com eine – erotisch durchaus gelungene – Website mit Videos, die allein Großaufnahmen der Gesichter von Männern und Frauen bei Sex und Orgasmus zeigen und somit das Konzept von Andy Warhols „Blow Job“-Film serialisieren, in rekursiver Anwendung von Warhols Ästhetik auf sich selbst. Scheinbar fließend gehen Milieus, Rollen und Interessen von Kunst und Kommerz, Künstlern und Sexarbeitern, Sexindustrie und Kulturkritik ineinander über: Fotomodelle und Sexperformerinnen auf suicidegirls.com oder abbywinters.com diskutieren über feministische Literaturseminare, die Künstlerin Dahlia Schweitzer ist zugleich Electropunk-Sängerin, Buchautorin, Ex-Callgirl, Fotokünstlerin und eigenes Aktmodell mit College-Abschluss in Women’s Studies, während umgekehrt sich die Geisteswissenschaften in Gestalt von Porn Studies und den jüngsten „Netporn“- und „Post Porn Politics“-Konferenzen dem Gebiet in teilnehmender Beobachtung annähern.

Dies geschieht um den Preis der Konfliktvermeidung. Ob als Provokation, Ausdruck der Macht des Sex oder von Geschlechterpolitik – es war das nunmehr liquidierte Obszöne, das die Schnittpunkte experimenteller Künste und gewerblicher Pornografie markierte, bei Courbet und Duchamp, in Batailles Romanen, Hans Bellmers Puppen, dem Wiener Aktionismus, Carolee Schneemanns „Meat Joy“, aber auch bei später zu Kunstehren gekommenen Pornografen wie den Fotografen Nobuyoshi Araki und Irving Klaw, dem Fetish-Comiczeichner Eric Stanton und den Sexploitation-Filmern Russ Meyer, Doris Wishman, (dem von Aïda Ruilova auf der letzten Berlin-Biennale gewürdigten) Jean Rollin und Jess Franco.4. Obszön in diesen Konstellationen sind Fetische, die zu Tauschobjekten zwischen Porno- und Undergroundkultur werden. In seinen Überblendungen von Biker-, lederschwuler S/M-Kultur, Satanismus und faschistischer Ikonografie spielt Kenneth Angers Experimentalfilm „Scorpio Rising“ 1964 diese Tauschgeschäfte beispielhaft durch. Zurück in Jugendkulturen kopieren sie ein Jahrzehnt später Genesis P. Orridges und Cosey Fanny Tuttis pornografische Performancegruppe COUM Transmissions, aus der die Band Throbbing Gristle und die Industrial Music hervorgeht, sowie die Punk-Mode, die Vivienne Westwood in ihrer Londoner Boutique „SEX“ aus Bondage- und Fetisch-Accessoires collagiert.

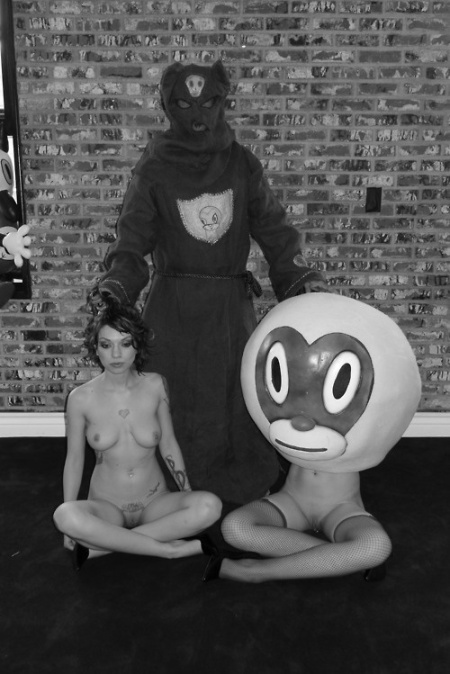

McLarens und Westwoods Punk ist negativ gewendete bürgerliche Empfindsamkeitskultur, die die Register des Hässlichen, des Ekels und des Obszönen gegen das Schöne ästhetisch in Stellung bringt. Umso weniger verwundert es, dass er in seiner späteren, nicht minder bürgerlichen Mutation zur Autonomenkultur besetzter Häuser, Wagenburgen und Kulturzentren nunmehr ein anderes, „alternatives“ Schönes für sich reklamierte. In derselben Logik wandeln sich, von den Sexbühnenshows der frühen Hardcore-Punkband Plasmatics mit der Frontfrau Wendy O. Williams, einer Ex-Stripperin und Pornodarstellerin, und später der Punk-/Metal-Frauenband Rockbitch bis zum vermeintlich punkkulturellen „Indie Porn“ im Internet, die Konnotationen der Fetische vom Obszönen zum Anti-Obszönen. Spezialisierte Pornowebsites etablieren in den 1990er Jahren „Gothic Porn“ als Genre, mit ansonsten konventionellen Pornobildern und -videos von Frauen im Dark-Wave-Look. Aus ihrem Umfeld geht 2001 „Suicide Girls“ hervor, die erste erfolgreiche kommerzielle Indie-Porn-Website.5.

Doch im linksradikalen Alternativgewand verleugnete Punk seine fetischistischen Wurzeln oder zeigte vielmehr seine Kehrseite, die Spike Lees Film „Summer of Sam“ bereits für die späten 1970er Jahre mit ihrer Konkurrenz von Punk und Disco nachzeichnet und in der die Punkkultur – männlich, weiß und heterosexuell dominiert – ihre Ressentiments gegenüber der polysexuellen, schwul geprägten und multiethnischen Discokultur pflegte. Der abschätzige Refrain „Samstag Nacht, Discozeit/ Girls Girls Girls zum Ficken bereit“ der deutschen Polit-Punkband Slime drückte 1981 eine Haltung aus, die sich sechs Jahre später und auf dem Höhepunkt der feministischen „PorNo“-Kampagne im Berliner Eiszeit-Kino gewalttätig entlud, als ein autonomes Rollkommando eine Vorführung von Richard Kerns und Lydia Lunchs Underground-Pornofilm „Fingered“ stürmte. Selbst heute noch arbeiten sich Pornografie-Diskussionen an diesem Konflikt ab, wenn auch weniger ausdrücklich. Proklamationen alternativer pornografischer Kultur und Imagination sind immer auch, und nach wie vor, Stellungnahmen gegen Anti-Porno-Feminismus. Und neben kommerziellen Gothic-Porno-Seiten hat die Indie-Pornografie ihre Ursprünge in jenem „sex-positive feminism“, der von Susie Bright, Diana Cage und anderen als Gegenbewegung zur PorNo-Kampagne Andrea Dworkins, Catharine MacKinnons und, hierzulande, Alice Schwarzers gegründet wurde und der zum Beispiel in der lesbischen Zeitschrift On Our Backs, im Jahrbuch „Das heimliche Auge“ des deutschen Konkursbuch-Verlags und auf der Website Nerve.com eine feministisch reflektierte, „andere“ Pornografie nicht nur diskutierte, sondern auch praktisch schuf.

Beide feministische Tendenzen, Anti- und Pro-Porno, unterscheiden sich zwar in ihrer Therapie, nicht aber in der Diagnose, dass Mainstream-Pornografie sexistisch und abstoßend sei.6. Übersehen wird dabei vor allem in Europa, dass Dworkin und MacKinnon mitnichten Verbot oder Zensur von Pornografie forderten.7. Vielmehr würdigt ihre Kampagne die Macht des Sex und der obszönen Imagination – jene Macht, die in praktisch sämtlichen Varianten alternativer Pornografie zum folgenlosen Spiel verharmlost, rationalisiert und verdrängt wird. An die Stelle einer Rhetorik des Künstlichen in der klassischen Mainstream-Pornografie – künstlicher Körperteile, steriler Studios, hölzernen Schauspiels – tritt in der Indie-Pornografie eine Rhetorik des Authentischen: Statt maskenhafter Normierung von Körpern durch Make-up, Perücken und Implantate wird die authentische Person bloßgestellt und, im Vergleich zum Gonzo, nicht mehr physisch, sondern psychisch ausgestülpt. Indie-Porno-Websites, wie sie die Seite http://www.indienudes.com umfassend verlinkt, emulieren nicht mehr die Cover-Ästhetik von Pornovideos und -heften, sondern haben auf ein Standardformat von Tagebüchern, Blogs und Diskussionsforen umgestellt, auf dem Nutzer mit Fotomodellen und Fotomodelle untereinander kommunizieren, in einem rationalisierten Diskurs vermeintlichen gegenseitigen Respekts bei simultaner totaler „authentischer“ Zurschaustellung der privaten Person, in genau jener Logik, die Foucault für die Entwicklung des Strafvollzugs von der physischen Verstümmelung bis zum Psychoterror des modernen panoptischen Gefängnisses nachzeichnet.

In dieser Personalisierung und Psychologisierung vollzieht Indie-Porno den nächsten logischen Schritt einer fortschreitenden Demaskierung pornografischer Akteure, der mit der (im Film „Boogie Nights“ episch nacherzählten) Umstellung von 35-mm-Pornokinofilmen auf billiges Video in den 1980er Jahren begann, sich im Gonzo-Analporno fortsetzte und in der Internet-Pornografie kulminiert. Der Gonzo-Porno ist insofern sogar subversiver und transgressiver als Indie-Pornografie, als er schwules Begehren im heterosexuellen Mainstream unterschwellig bedient und etabliert: analer Barebacker-Sex, drag-queen-artig gestylte Frauen und – im Gegensatz zu den meisten Pornos der 1970er und 1980er Jahre – offensiv sexualisierte männliche Stars wie Rocco Siffredi im Fokus der Kamera. Was im Gonzo -als radikale poiesis und proletkulturelle „Jackass“-Körperperformance inszeniert wird, wandelt sich im Indie-Porno zur empfindsamen Beichte mit dem zahlenden Publikum als voyeuristischen Beichtvätern, bei ständiger Vergewisserung der bürgerlichen Normalität und, unabhängig vom Härtegrad, spielerischen Harmlosigkeit des gezeigten Sex.

So, wie Indie-Pop nur eine Scheinalternative zum musikindustriellen Mainstream ist und in Wahrheit auf demselben Geschäftsmodell basiert, das durch immer absurdere Urheberrechtsgesetze, Verhinderungstechnik, Abmahnungen und Hausdurchsuchungen abgesichert wird, ist auch Indie-Porno mitnichten „unabhängig“, sondern kommerzialisiert und von freien Kanälen abgeschottet, ja sogar strategisch gegen diese positioniert: Gerade weil Mainstreamware problemlos in Peer-to-Peer-Tauschbörsen zu haben ist, wird Pornografie, wie Popmusik, nur noch durch Differenz verkaufbar, einschließlich jener zu sich selbst.

Anmerkungen:

1. „Sex ist das Spiel der Erwachsenen“, Interview im Tagesspiegel, 2. 7. 2006

2. Vgl. Mark Terkessidis, „Wie weit kannst du gehen?“, in: Die Tageszeitung, 18. 8. 2006.

3. Peter Gorsen, Sexualästhetik, Reinbek 1987, S. 481 ff.

4. Porno und Kunst verschmelzen bei Otto Muehl, dessen formelhaft sexistisch-voyeuristische Materialaktionen einerseits Logik und Bildsprache des Mainstream- und Scat-Fetischpornos vorwegnahmen und der andererseits an den Sexploitation-Filmen „Schamlos“ (1968) und „Wunderland der Liebe – Der große deutsche Sexreport“ (1970) mitwirkte; einen ähnlichen Weg beschritt 1981 der Schlagersänger und spätere Sexguru Christian Anders mit seinem Film „Die Todesgöttin des Liebescamps“.

5. Weniger bekannt ist, dass der Hustler-Verleger Larry Flynt mit „Rage“ bereits 1997 ein Pornomagazin im „Alternative Pop“-Stil in Fotos, Typografie und Texten auf den Markt gebracht, aber kurz darauf wieder eingestellt hatte. Heute arbeitet Joanna Angel, Betreiberin der Indieporno-Website burningangel.com, für Flynts „Hustler Video“.

6. Oder sie schließen sich, wie in Catherine Breillats Filmen, zur Synthese kurz, dass Sexualität zwar per se sexistisch sei, daraus jedoch abgründiger Lustgewinn erzielt werden könne.

7. Siehe dazu Barbara Vinkens Vorwort zu Drucilla Cornell, Die Versuchung der Pornographie, Frankfurt/M. 1997.

PREFACE

While preparing this issue of Texte zur Kunst, we were confronted not only with the ongoing topicality of explicit or drastic depictions of sexuality in art and pop culture but also with a host of conferences, films and festivals on the theme of „pornography“. In Berlin, the „Post Porn Politics“ conference held at the Volksbühne aroused considerable attention in the art sections, while the first porn film festival took place accompanied by the CUM2CUT Indie-Porn-Short-Movies-Festival, during which the participants provided with digital cameras were asked to shoot heterosexual, gay, lesbian, or transsexual DIY porn movies on three consecutive days anywhere in the city („Enjoy the pleasure of sharing pornography all over the city“). Obviously, pornography is booming – both in the mainstream and in so-called independent contexts and in theoretical debates revolving around subjectivity and the politics of identity, to say nothing of the porn industry flanked on the Internet by innumerable individual blogs pandering to all niches of sexual desire and fantasies. At present, the range of approaches in theorizing pornography or criticizing it, is as diversified as the depictions of sexuality themselves which are subsumed under this term.

For quite some time, the feminist debates concerned with pornography were characterized by the antagonism of anti-porn and anti-censorship positions, where on the one side the misogynous aspects of heterosexual pornography – at times also causalities between pornographic scenarios and rape statistics – were stressed, and on the other the right to freedom of speech and expression vis-à-vis attempts at censorship was brought to bear. At the beginning of the 1990s, with publications such as „Hard Core“ by Linda Williams, who in 2004 followed up with an anthology programmatically titled „Porn Studies“, a paradigm shift commenced under the influence of models of textuality all the way to questions pertaining to the historically variable conventions, mediums and aesthetics of pornography as a genre – through which porn tended to lose its status as an alleged transgression of social norms and became a subject of academic research. In Williams’ words, porn changed from a position of „ob/scene“ to one of „on/scene“. The term „postporn“, coined by the American artist and former porn actress Annie Sprinkle and the French theoretician Marie-Hélène Bourcier totally contradicts the „PornNO“ campaigns of the 1970s and 80s and ultimately stands for the attempt to develop alternative sexual economies by means of pornographic mises en scène that lie beyond normative ascriptions of identity. In this context, pornography is not understood as a specific genre. Instead – for example, in the works of the French theoretician Beatriz Preciado – references are made to the aesthetic practices of performance art via gestures of queer self-empowerment, thus positioning the lively presence of sexualized bodies against the pornographic logic of visual pleasure and consumption

.

However, the majority of the artists who in the past years have dealt with pornography seem to follow the assumption that under the present economic and technological conditions an outside of pornography can no longer exist – a hypothesis which was recently discussed under the catchword of the „pornographization“ or „pornoization“ of society, for example, by Mark Terkessidis in the taz daily newspaper in which he made reference to the „regime of a permanent overtaxing“ of female performers staged in the increasingly harder gonzo films in analogy to neo-liberal working conditions. Today, attempts at censorship, as in the case of Robert Mapplethorpe’s gay S/M stagings in the 1980s in the United States, are hardly encountered anymore in the field of art. One can instead discern that pornography in the „salons of high culture has become worthy of depiction“ – as it was formulated in the current issue of the art magazine Kunstjahr for 2006. Even if the present „porn boom“ in art and pop culture is not a provocative expansion of the bourgeois art canon by sexually-charged motifs, but instead a reflex to – and in some cases a reflection on – the desires of the art market, artists from Vanessa Beecroft, David LaChapelle and Jeff Koons, to Richard Philipps, Richard Prince and Thomas Ruff, all the way to Larry Clark, Tracey Emin and Andrea Fraser have for quite a while now discovered pornography as a field in which analytical-critical distance and the affective involvement on the sides of both the producers and recipients meet and can be utilized. Against this background, the contributions of this issue, which we conceived together with Diedrich Diederichsen, attempt to approach the theme of pornography in art, pop, independent culture, digital media, and critical theory, and take stock of the current state of (identity) political debates on the explicit depictions of sexuality.

SURVEY ON PORNOGRAPHY

For quite some time now, an increase of explicit, obscene and drastic depictions of sexual practices can be observed in art, popular culture, fashion photography, literature and film – a boom that goes along with an accelerated dissemination of pornographic material through a segment of the visual industry operating in various media formats. At the same time, pornography advanced to become a category for cultural analysis, occassionally for cultural critique. In reference to the term „pornographization“ for instance structural parallels are being drawn between the pornographic production of affects and neo-liberal capitalism, or the television broadcast of 9/11 is being compared with the „effet du réel“ of pornographic videos. Thus pornography is less regarded as a specific genre but as a cultural logic or political principle within the contemporary regime of visibility. Since the early 90s feminist debates on pornography shifted from a focus on the antagonism between anti-censorship and anti-porn positions towards discussions of the subject-theoretical implications of pornography as a part of mainstream culture – which on an institutional level led to the introduction of „porn studies“ at US-American universities. At the moment, pornography no longer appears as a genre that transgresses the limits of academic or non-academic cultural analysis, but as a phenomenon whose conventions and aesthetics can be both historicized and theorized as well as appropriated against the backdrop of identity politics. Especially in the current field of „post-porn politics“, the performative potential of pornography is emphasized in order to challenge normative attributions of identity and technologies of power centered on sexuality by means of queer „body politics“. Against this background, the question needs to be raised what the different (programmatic) investments of feminist, (identity-)political and pop-cultural debates in pornography are.

How would you describe your approach to pornography? Do you agree with the thesis of an increasingly pornographic logic of social relations and political conditions? Has the critique of pornography become obsolete in the face of claims of its immanent emancipatory potential? Why Porn Now?

FRANCES FERGUSON

In the work I have done on the topic of pornography, my effort has been to describe a cultural logic of display and to try to explain the workings of the differential character of that display in articulated social environments. If, I wondered, the world is always visible, why do we see certain aspects of it with what feels like emphasis?

This issue has frequently been framed in terms of a generalized politics of recognition, in which certain types of individuals-women, queers, servants, members of ethnic and racial minorities-are said to be treated unjustly because they are said to be visible but effectively unseen. In this intensely metaphysical version of empiricism, the claim on behalf of individual political actors or, more simply, persons takes the form of a claim for a justice of visibility. The reality of (some) visible existence is said to be obscured by ideology. I found myself interested in Catharine MacKinnon’s account of pornography because it seemed to me to raise the question of visibility in tandem with the question of domination and subordination. Yet though MacKinnon sometimes uses phrases like „a culture made by pornography,“ I came to think that she had too great a stake in evaluating individual cultural objects and to evaluating them in relation to what she took to be their explicit statements and, specifically, how they might be said to forward (masculine) domination and (female) subordination. Thus, while I see that she is not objecting to pornography on the old grounds of sexual morality and prudishness, I think that her approach-which makes significant claims to be a general theory of the domination of men and the subordination of women that distributes reality to men and a combination of compulsory exposure and invisibility to women-ultimately relies too heavily on local examples and the collection of many examples as if they all conduced to the same point. A reader’s evaluation (hers) is for her, as in aesthetic claims, the last word.

Because I work in the field of literary studies, I recognize the appeal of pointing to a particular work and saying, „There it is. Everything I’m talking about-everything important in the world–is expressed in this work.“ Using texts and images as epitomes is a useful thing. But I also found myself thinking that the history of reception needed to be taken into account. In talking about the history of reception of literary works, I don’t mean to accept the libertarian view that we can chart our progress along a path of sexual enlightenment and congratulate ourselves for being more advanced than the Victorians or other similarly sexually retrograde groups because we tolerate sexual explicitness that they would have pushed underground. Rather, I would argue that the varieties of accounts of texts and images suggests that identifying a stable, universal, and transhistorical meaning for individual texts and images is a chimerical project. The devil knows how to quote scripture, scripture knows how to quote the devil, and readers and viewers have very different views about which one is speaking when.

Yet the variation in understandings of texts and images by no means pushes us to a simple relativism in which anyone can plausibly say anything about anything at any time. And it was in the service of this point that I concluded my book on pornography with a brief discussion of Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho. In part, I was interested in the fact that in the space of only one decade the book had gone from being castigated to being praised (and by some of the same people). I thought that such a rapidly changing reaction was significant for helping us to understand the systematics of pornography and the way in which individual cases are taken up and discarded in reception. The words on the page hadn’t changed in the decade in which American Psycho went from being treated as scurrilous to being treated as the work of a moralist (as Swift and Flaubert and Dostoevsky were moralists). So, I wondered, why was the reception so different in 1991 and 2001? Part of what I concluded was that American Psycho was the latest instance in a series of instances (going back to Sade’s novels) in which what feels most shocking about a work is the feeling of intense contemporaneity it temporarily establishes-its making us feel as though we share the time and place of its represented world to such a degree that we feel as though our ability to achieve detachment is compromised. American Psycho intensely achieved that sense of contemporaneity for a time by presenting itself almost as if it were a narrativized advertising catalog, complete with pedantry about then-current brand names and then-current celebrities and extraordinary ignorance about anything happening more than a few miles and a few months from the world in which the novel’s persons (and readers in 1991) move. In my work on pornography I tried to call attention to the ways in which the things that we treat as pornography represent a genre not simply because of their content-their sexual explicitness or their sadism-but also because they feel closer to us than other texts or images. And I tried to provide a fuller explanation for that feeling of proximity by talking about how a writing that uses the name pornography for itself appears at the end of the eighteenth century in western Europe (for the first time since late Roman antiquity) at just the moment at which utilitarianism is developing an account of how the interactions between an actor and an environment conduce to a new view of action, one in which individuals contribute actions within organized social groups and come to discover the value of those actions within those groups.

Like Roland Barthes, I saw deep affinities between Sade and Fourier and their efforts to articulate environments that would capture and evaluate even small actions (and increasingly call out more extreme actions through the operation of their comparative logic). And seeing that conjunction between Sade and Fourier and their ways of thinking about closed environments also suggested to me an account of Benthamite utilitarian structures that represented a revision of Foucault’s influential view of them. For utilitarian social structures are important for helping us to understand that there is more to the commodification of action than we capture in talking about the value of labor. They help us to understand why some actions-even minimal ones-can have enormous effects in a narrowly defined environment (and, hence, why one can plausibly make the argument that even the sight of a closed book might constitute a sexual threat). As I was trying to demonstrate the importance of utilitarian social structures (schools, workhouses, prisons in the early utilitarian phase; schools and workplaces today) in our understanding of how the value of persons and their actions have been registered in particular display technologies, I also came to appreciate the difference between an environment and a world. We live in a world, but an environment both works on us and contributes very significantly to the ways in which we work and the way in which we and other people register the value of our work. When Ellis’s novel is clearly just part of the world (as it comes to seem historical and, indeed, to call out for footnotes that would identify some of the already archaic brand names), it has less weight for us than when it would if it could really constitute itself as an environment-which is merely to say that the sorts of deontological projects that Bentham was pursuing have an importance even for apparently untheoretical practices like pornography, because they help us to think about the degree of force that an environment exercises in relation to individual actors, actions, and objects and about what is necessary for an environment to function to add or extract value from them.

LEE EDELMAN

There’s a paradox in the discourse on pornography that I want to emphasize at the outset. Pornography, in order to count as such, can have no redeeming or aesthetic value except insofar as it poses a challenge to the value of the aesthetic. But that challenge, to the extent that it weighs one measure of value against another, itself partakes of the aesthetic imperative that pornography disdains. This paradox has significant consequences for what I’m proposing here: that pornography, like queerness, implicitly gestures toward the advent of the posthuman and so to the end of the knowledge regime that promulgates normativity. For to read pornography as a challenge to the aesthetic principles of unity and coherence, and so as a challenge to the values essential to the concept of „the human“, is to remain, by virtue of the privilege accorded to the possibility of reading, fully „within“ the domain of „the human“, fully committed to the epistemological mastery, to the wrestling of sense from substance, that pornography undoes. It’s to reaffirm, intentionally or not, the logic of legibility that makes our formation as subjects always an aesthetic education, one that represents the universe as single-mindedly pedagogical, constantly enforcing the spiritual value of making matter mean. Pornography, it follows, can never, properly speaking, be „read“ at all. The porneme, the essential unit of pornography, the fundamental element of its resistance to cultural law, is banished by interpretation, disappearing as soon as we try to elicit a cultural profit from it. However widely available or frequently encountered it may be, then, pornography never operates as a normative cultural product.

It refuses the „principle“ of culture, the aesthetic imperative of growth and development, of maturation or ripening into wholeness. It refuses the totalization always implicit in „the human“, a term that serves, in the framework of our aesthetic education, as the universal sign of the aesthetic as our universal value (the value, precisely, of conceptual unity, coherence and epistemological mastery). As an aesthetic category, „the human“, moreover, gives rise to the inhumanity of excluding some people, those viewed as threats to its particular universality, from the ranks of „the human“ itself. Pornography, by contrast, contributes to what I describe as the queer event: the event of „dehumanization“ that resists the universal reproduction of value (and the universal value of reproduction), that insists on what Adorno often calls the non-identical, and that expresses itself in the anti-identitarian negativity of the death drive. This queer event puts an end to“the human“ and the inhuman with a single blow. Borrowing the concept of a truth event from the work of Alain Badiou, I mean to claim that pornography, to the extent that it’s faithful to the porneme, to the anti-social transgression at stake in pornography’s basic unit, attests to what we’re still unable to cognize or to recognize: the end of the era of the human.

But like every conservative battle cry, „the human“ enjoys the advantage of affirming what we think we already know: the universal value of constructing ourselves through abstract universals endangered by the solicitations of the local, the transient, and the queer. Adverting us to this danger, „the human“ survives on the pathos of its putative vulnerability. Any attempt to question it, let alone to deconstruct it, has the force of a violent assault upon its categorical integrity, eliciting, in turn, the pathos that „the human“ always invokes. Paradoxically, then, interrogation of „the human“ merely reinforces it, letting it draw new strength from the prospect of its possible dissolution. Its undoing thus always eludes us and its posthumous survival, after our „knowledge“ of its death, turns us, the „posthumanous“, into specters, aesthetic ideology’s afterimages, ghosts who endlessly haunt ourselves and cling to our phantom identities with a ruthless sentimentality and a stubborn faith in the sublimations that „the human“ as concept intends.

The porneme refuses such sentiment, offering in its place the mindless, machine-like pulsions of the drive – the drive whose automatism inverts the elevations of the sublime. Where the Kantian sublime grants tranquility in the face of a threatening infinitude, affirming the power of the subject to comprehend and so to master it, the drive strips the subject of mastery, depicting that subject, instead, in the steady grip of the drive’s relentless force. Pornography contributes to the queer event by desublimating „the human“. For what threatens most fully the universalizing ideal implicit in „the human“ is the realization that there’s nothing so extreme, so disgusting, so unthinkable that it can’t serve to mobilize the libidinal drive of some from among our neighbors. The terror that realization provokes, as we see in Freud’s „Civilization and its Discontents“, responds to the radical particularity of each subject’s encounter with jouissance, with the Real. And doesn’t that radical particularity bespeak a universal queerness at odds with the „particular“ universal enshrined in the normativity of „the human“? Pornography marks our subjection to the universal queerness of the drive, but promises no liberation from our bondage to „the human“. What binds us to it more thoroughly than the fantasy of escaping it, the fantasy of attaining to freedom through the power of the mind? The posthuman, were it possible, would not be possible for „us“, destined as we are to wander in the desert of „the human“, destined to preserve, „posthumanously“, a concept we’ve outlived. The queer event, the dehumanization pornography attests to, remains, therefore, unthinkable at the moment it’s taking place. I described in my most recent book, „No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive“, the „impossible project“ of refusing the governing logic of futurity that constitutes the political field in heteronormative terms. The queer event, I’m suggesting here, moves beyond futurity toward a politics not determined by the subject of aesthetic value, a politics of dehumanized subjects that we, the „posthumanous“, can no more make sense of than we can read or interpret the porneme that hopelessly heralds its approach.

STEVEN SHAVIRO

Why Porn Now? In fact, I don’t believe that Now is the time. Of course, there’s more stuff available these days than ever before: extreme porn, gonzo porn, DIY porn, and what have you. Explicit images are everywhere. No fetish, no kink is so obscure that you can’t find a group devoted to it on the Net, complete with ready-to-download videos. But I find it hard to regard all this as a triumph of anything besides niche marketing. Today, in the era of globalization, electronic media and post-Fordist flexible accumulation, everything is a commodity. We have reached the point at which even the most impalpable and evanescent, or intimate and private, aspects of our lives – not just physical objects, but services and favors, affects and moods, styles and atmospheres, yearnings and fantasies, experiences and lifestyles – have all been quantified, digitized, and put up for sale. It’s true, of course, that there are many social forces opposed to the proliferation of pornography, and more generally of sexual fantasies and possibilities. In the United States, voters routinely approve anti-homosexual ordinances, and politicians and preachers score points by demanding action to stem the flood of „obscenity“. But really, isn’t this hysterical moralism just the flip side of marketing? The main effect of these crusades is to give pornography, and more generally all forms of nonprocreative sex, the shiny allure of transgression and taboo. And that, in turn, only serves to stimulate the consumer demand for porn-as-commodity, and sex-as-commodity …

In fact, there is nothing more banal than the spectacle of a right-wing politician who turns out to have a passion for teenage boys, or the minister of a fundamentalist megachurch who is discovered to be hiring rent boys on the side. (I cite only the two most recent of the incessant pseudo-scandals that make headlines in the American media.) It’s no longer possible to understand these pathetic closet cases in terms of Freudian repression, or the Lacanian Symbolic, or any of the old categories of depth psychology. Rather, their logic is a commodity logic: fetishism in the Marxist sense, instead of the Freudian one. All our affects and passions are perfectly interchangeable, subject to the law of universal equivalence. That is to say, all of them are commodities, detached from the subjective circumstances of their affective production, and offered up for sale in the marketplace. Today our fantasies and desires – indeed, „our bodies, ourselves“ – seem to be outside us, apart from us, beyond our power. And this is a very different situation from that of their being repressed, and buried deep within us. Commodities have a magical attraction – we find them irresistible and addictive – because they concretize and embody the „definite social relations“ (as Marx puts it) that we cannot discover among ourselves. In the fetishism of commodities, Marx says, these social relations take on „the fantastic form of a relation between things“. The secret sex life of the right-wing politician or preacher is thus a sort of desperate leap, an attempt to seek out those social relations that are only available in the marketplace, only expressible as „revealed preferences“ in the endless negotiations of supply and demand. In short, such a secret life is nothing more (or less) than a way of getting relief by going shopping – which is something that we all do. This realization dampens down whatever „Schadenfreude“ such incidents might otherwise afford me.

Therefore, I don’t accept „the thesis of an increasingly pornographic logic of social relations and political conditions“. To the contrary: there is nothing exceptional, central or privileged about pornography and the „pornographic“ today. Pornography simply conforms to the same protocols and political conditions, the same commodity logic, as do all other forms of production, circulation and consumption. Porn today isn’t the least bit different from cars, or mobile phones, or running shoes. It embodies a logic of indifferent equivalence, even as it holds out the thrilling promise of transgression and transcendence – a promise that, of course, it never actually fulfills. Is it possible to imagine a pornography freed from this logic? Perhaps some recent writings by Samuel R. Delany provide an alternative. In novels like „The Mad Man“ and „Phallos“, Delany envisions a sexuality pushed to the point of extremity and exhaustion. There are orgies of fucking and sucking, elaborate games of dominance and submission, and episodes of violence and destruction, together with enormous quantities of piss and shit and sweat and cum. Yet there’s no sense of transgression in these texts. Instead, the meticulously naturalistic thick description places these episodes firmly in the realm of the everyday. Delany presents „extreme“ sex as a form of civility and community, an adornment of life, a necessary part of the art of living well. Delany’s is the only writing I know that answers Michel Foucault’s call for an ethics/aesthetics of the body and its pleasures, freed from the dreary dialectics of sexuality and transgression. As such, it provides an alternative as well to the relentless commodification that permeates every corner of our postmodern existence.

MARC SIEGEL

You ask about my approach to pornography, about my investments in it. For starters: I like it. Let me specify … For a number of years now, I have tended to prefer written over visual pornography. Ever since I got a high-speed internet connection, I’ve gravitated toward reading pornographic stories on-line and downloading them for future use. Typically, I choose those categorized as „Bisexual“ – although I would never categorize my non-porn hours in that way – and subcategorized as either „Anal“, „Fetish“, „Loving Wives“, or „Urination or Stories Where Raunch Is a Primary Plot Element“. Within these sub-categories, the stories that turn me on the most tend not to be too literary. I’m not interested in long-drawn out reasons (historical, psychological etc.) for the sexual acts described in the stories. A simple set-up is usually sufficient. I treat the search for the good story as a kind of foreplay, as it were, so that when I finally find one that interests me, I’m so turned on that I want to get right down to the explicit sexual scenario and not wade through a long literary set-up. Since the onset of computer pornography, this foreplay to masturbation, which is of course an aspect of masturbation itself, incorporates and in the process eroticizes the technical apparatus of my computer: keyboard, mouse, screen, software program etc.

When I used to masturbate while reading Boyd McDonald’s „Straight to Hell“ (STH) chapbooks of true homosexual experiences, my foreplay consisted of walking to my bookshelves, looking for the right „STH“ volume, taking the book with me to a good place to sit or lie down, and flipping through the pages with one hand in order to find a particularly hot account of sex. This whole process of anticipating the hot story – be it „He Said He Preferred Women“ or „Swills a Dozen Loads of Piss“ – turned me on and set the stage for the masturbation that followed. In the internet age, however, my masturbatory foreplay consists primarily of stretching out my arm to reach for the mouse, then moving it around while watching the little black arrow click on the circle with the blue-green „N“ in it; watching the circle turn black while the Netscape window opens up on the screen; typing in the address of the particular story web site I’m interested in (either nifty.org or literotica.com); and clicking and dragging my way through the stories to find the ones that appeal to me. I’ll skip further technical details and just end this account of my approach to pornography with the observation that the internet has enhanced – though not radically altered – the ways in which I fulfill myself sexually and has thereby enriched my sex and fantasy life.

I’m trying to specify what kind of pornography I like at the moment. In doing so I hope also to make it clear that I consider as pornography sexually explicit material intended primarily for purposes of sexual arousal. I don’t like to use the word pornography to describe a „logic of social relations and political conditions“, as you put it in your question. I know that some theatermakers here in Berlin, for instance, are fond of doing exactly this. But, as their work attests, such hasty analogical uses of the word pornography often betray – or at least leave unquestioned – an assumption that pornography is a debased form of social relations. In a rush to analogy, I sense a „we all know what that is“ perspective towards pornography. But I don’t think „we all know“ what pornography is, what it can be, and how it functions. (Which pornography are we talking about? Hetero? Gay? Lesbian? Bi? Tranny? Ethnic? SM? Scat? Written? Visual? Aural?)

Thanks to some conferences, film festivals, workshops, books, occasional university courses and the emergence of what the French theorist Marie-Hélène Bourcier calls „post-porn“, we are beginning to develop both a critical vocabulary for speaking about sexually explicit images and a critical practice of making them (better). But these scattered attempts to take pornography seriously as a cultural phenomenon hardly constitute a field. Porn studies is the optimistic title of a wonderful anthology by Linda Williams, but it is not – as far as I know – the name of a university department or program in the US. (If only it were.) Furthermore, post-porn, in Bourcier’s useful formulation, does not describe a logic of our contemporary political situation, if by that we mean a logic that denies porn its specificity as sexually explicit and arousing or that situates porn beyond critique and analysis. To the contrary, as Bourcier sees it, post-porn describes those all too few cultural products – the film „Baise-moi“ by Virginie Despentes and Coralie Trinh-Thi, the films of Bruce La Bruce and the work of Annie Sprinkle – that engage critically with pornography from a feminist perspective. Post-porn cultural work, so Bourcier, challenges the segregation of arousing depictions of explicit sexual acts from other modes of representation and at the same time reimagines gender and sexual difference. My take on pornography? Post-porNOW!